|

|

|

||

|

|

Ulsterheart Chapter 1 (Kilgreen Dawn)

pages 1 through 5

Page 1

Kilgreen Dawn "heaven peep through the blanket of the dark" (Shakespeare's Macbeth)

Midway between Bangor and Bundoran; midway between Foyle and Sheelin; midway from Neagh to Erne, and from Donard to Errigal—in the very heart of old Ulster—Kerog. Kerog is now the crossroads of Ulster, where Belfast-Enniskillen and Newry-Derry highways intersect, but the Clogher Valley was always a highway—and at the Valleytop— Kerog!

THIS ANCIENT PARISH consisted of over 10,000 Irish acres between the Owenbrack river north of Dunmoyle, and the river Blackwater near the U.K. frontier. Westwards it extended from 'alpine' Martray lough to the Retting Burn beyond Garvaghy. And as Tyrone novelist Carleton assures us "Everyone knows the Routin Burn and the purty knoll beside it where Jack McGuinness played cards with the Devil."1 Right down its middle and past Kerog Church flows the Ruckan Stream to meet the Blackwater beyond Lisnawery. Near their junction arrives the Enyr water after its crescent through Grange and Lisdoart. The Ulsterheart Church is neatly set where converge two pleasant Tyrone glens—Glencul and Glenhoy Its Ruckan Stream marks the Bishop's border, and so a 17th century survey noticed "It meets the parish of Clogher on a brook called Ruckan," perpetuating, as its name implies, some frontier of primeval vintage. See Map I on page 402.

Across this parish for millions of years swam millions of fish, when the British Isles were under a swollen Atlantic. When sub-

|

|

thaw flooded all the lowlands from Neagh to Erne. Kerog became an inlet on this 50 mile lake. Sand and gravel deposits silted up and formed the eskers—a legacy for the concrete construction industry to exploit 20 thousand years later.

About 5,000 B.C. the waters eventually subsided, and Kerog was left a bleak desert of sludge and moss not likely to attract settlers.

The first people ever to come to Ireland settled around Larne and Coleraine about 6,000 B.C. Some of the primitive Bannsiders may have penetrated to the Blackwater via Lough Neagh. They could gaze across the Ulsterheart marshes, or hunt elk in Richmond. When road-builder Eric Hadden was cutting deep into Richmond Hill in 1960 to complete the village by-pass he uncovered some huge bones near the junction to the village. Much of the anatomy had already been deposited on the dump due west of the present Rectory before he recognised this fine set of antlers. The scapula of another elk was excavated by the same Contractor at the bypass bridge. The first groups to sojourn in the Ulsterheart were long-faced,

dark-haired, and medium-sized. Indeed the Four Masters, that great compendium of folklore and tradition records what it alleges is a passenger list of one such group which arrived in the Ulster-heart just after 3000 B.C. It tells of fifty women led by a lady called Cesair, and three men, Fintain, Ladra, and Bith whose name remains on the mountain where he was buried—Slieve Beagh—a few miles south-west of Kerog.

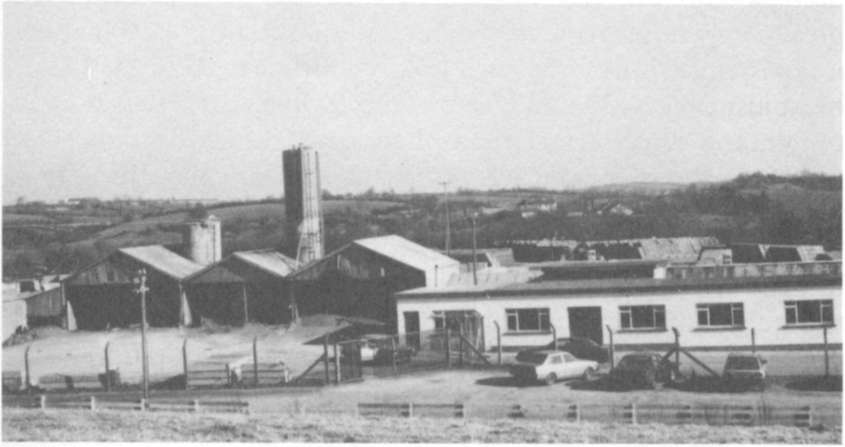

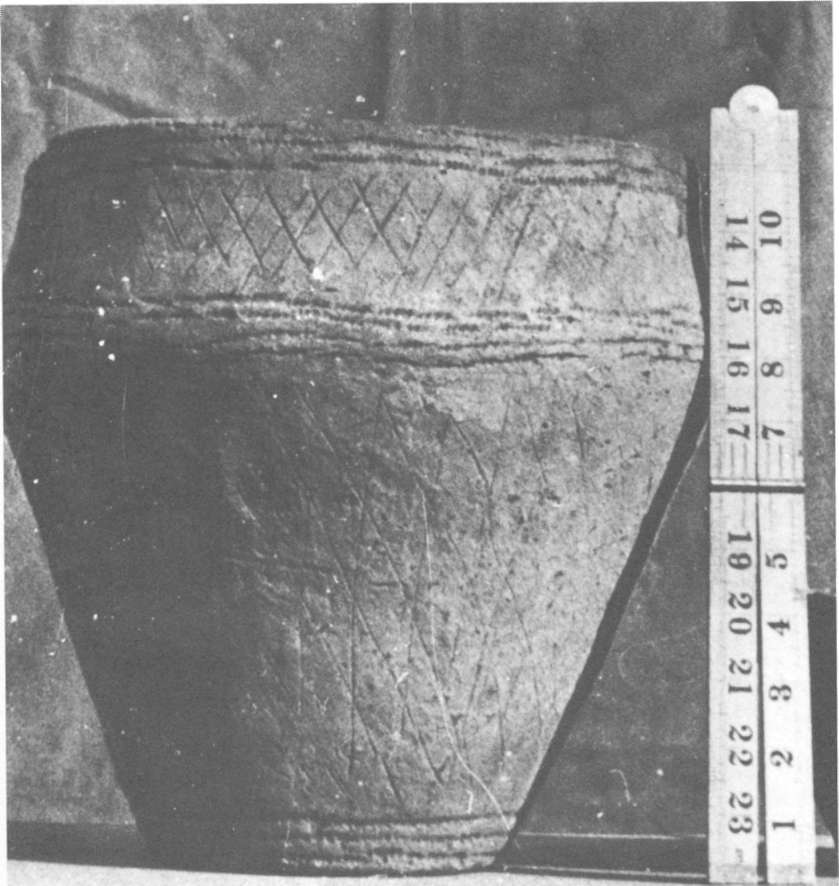

Few stone implements and utensils from the period have come to light in the district. Ballymacelroy clergyman Joseph Rapmund was quite a dynamic amateur archaeologist. About 1890 he found a stone hammer, and in Shantavny a very rare urn beautifully line-marked was unearthed. Then, on 3rd October 1959 Sarah McCaffrey of Greenhill heard that quarrymen behind Glencull School had come upon something. She alerted Dr. George Gillespie who, with all haste and caution, rescued the Glencull Urn. The Ballynany Axe was unearthed from the turf by Sam Alexander's father.

These early stone-agers did no tillage. They hunted for meat and furs. The last stone-agers were Kerog's first farmers. They had learnt to make bronze, and with axes of this copper-tin alloy they could hack their way into the lowland forests and till the fertile valley floor. As a schoolboy, David Coote came upon one of their axe-heads, lost it as children will, only to rediscover it at his Balnasagart home in January 1975.

Copper was plentiful, but not tin, in Ireland. Tin had to be brought north from Kernow (Cornwall). So began three thousand years of Kerog-Kernow contact.

Practically all we know of these bronze-agers' lives is in their deaths. Their huge stone burial cairns have survived the ages. Ulster's most spectacular sample is at Newgrange in the Boyne Valley. Knockmany—hill of the menhirs (huge stones) is not as elaborate, but it stands on a far loftier pedestal, as it broods over the western approaches to Kerog. Our most celebrated souvenir of these Bronze Age aristocrats is the five-foot pillar, decorated with undeciphered hieroglyphics, in Sess-Kilgreen. It shows about six stars, twelve spirals, twenty-four linear cups, and forty-eight distributed cups. There are a tossed cairn on Greenhill summit and enough

|

Then, in the autumn of 1973 the author discovered a fragment of tri-spiralled passage-grave art embedded in deep moss on the