Kerography

Pages 272 to 282

| Chapter 8 begins here |

|

"As down the westward slope of life we move Shapes from the past our daily steps attend; So live, that memory in thy age may prove No dread intruder,m but a welcome friend"

(Kells Ingram)

|

Page 272

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION got under way about 1750, but it was 1800 before its ripples seeped through to the Ulsterheart, when Landlords started rummaging in their fields for coal seams. In 1811 a family moved into Kerog with the vision and enterprise to put Kerog on the industrial map, had they not encountered rustic hesitancy and village timidity.

They had already built Stewartstown "with its fine square a monument to the town-planning genius of the Stewart family",114 and in 1726 they re-modelled Cookstown. Hayward, that connoisseur of Ulster topography, comments "its present remarkable appearance is the result of a very early experiment in town planning."115 In 1726 William Stewart built its one mile boulevard. "Nothing of the kind had ever been known in the country." And to crown their municipal enterprises they employed the Buckingham Palace architect Nash to design Killymoon Castle above the Ballinderry River.

John Stewart (1757-1825) was Attorney General for Ireland in 1799, and for his services at the time of the Union he was knighted in 1803.116 His mother was Sarah Hamilton, and it was Hamilton-Gorges property that Sir John Stewart took over in 1811, when he bought Ballygawley. He took up residence at the Harvey home in Tullygliss. He re-named it with what he thought was the English equivalent—Greenhill. The demesne in northwest Kerog he called "Ballygawley Park". In later years, his son added its stately Doric facade.

Page 273

From this base, the Stewarts built modern Ballygawley. For a thousand years settlers had clustered around the ruins of Moy Enyr monastery. They could use its weir at Grange Falls, and a few yards downstream the river was easily forded. Ringed by hills, it was a cosy glen. Small wonder it was known as 'the town of the glen'—Bally-glyn, and its name was first written down as Balle-galin.117 In 1773 the Pointz Hotel rose beside the whiskey making at Grange Falls, and seven years later the Coulter House went up where the track towards Omagh wound west to avoid the Knock (hill). Between these first large structures stood a cluster of hovels, but by the end of the century the whiskey men and merchants had a few two-storey houses.

Within five years of the Stewart arrival, the village increased from 90 houses to 140. Kelly Groves, describing the village in his 1817 report to the Shaw Mason office in Dublin, gave the credit to the Stewarts. "Under the encouragement this village has received from its present Landlord it has considerably improved, the population having materially increased within these latter years." The secret of their success was linen.

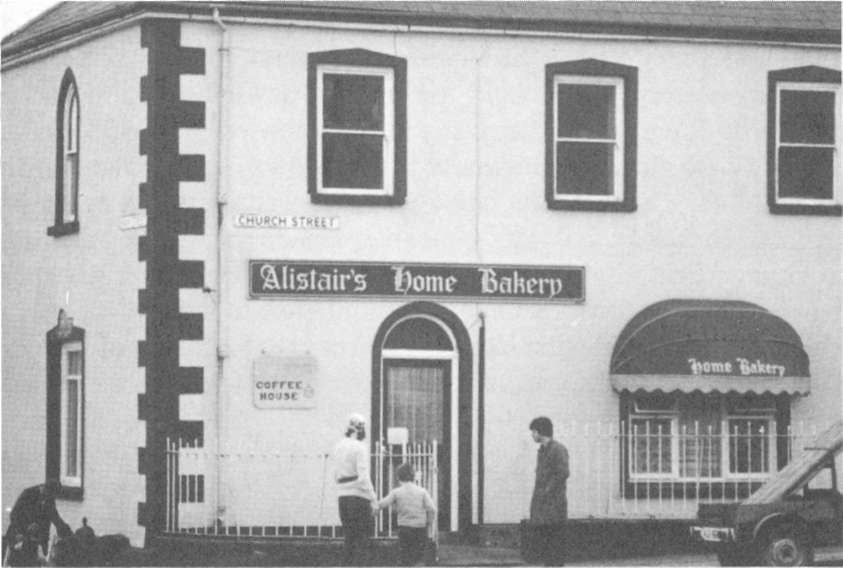

Right opposite the Coulter House they built a Linenhall with a drive-in where carts could unload in shelter. This archway is now windowed. In 1812, the Stewarts established a fortnightly linen Market. They believed in incentives. So they offered prizes of 15, 10, and 5 shillings for the greatest quantities sold, and 5 shillings and half-a-crown for the "best wrought pieces".118

The response was remarkable. Kerog weavers rose to the occasion. Some of them built new looms in their homes, and marshalled the whole family to take their turn with the shuttle. Some who had previously been Labourers or small farmers with a small loom for home needs, now made it their main occupation. In that very year, when Napoleon was marching on Moscow, Kerog weavers rushed their bales of cloth into the Linenhall. Each bale was 52 yards long, and the total sold in 1812 was 9,360 bales. Had the strips been joined end to end, the total sold in Stewart's Linen Mart in that one year would have stretched the 300 miles from Ballygawley to Birmingham. Clearly Kerog had the potential for becoming a new 'Banbridge' or even 'Belfasf in the Ulster midlands.

Page 274

|

The population explosion provided consumers for a softer beverage than that which flowed from the Distillery. So, the Brewery now set up by the Armstrongs was very likely a spin-off from the Stewart enterprise. Certainly they built a fine 36-foot bridge across the Enyr Water, and inscribed the year in a neat oval— 1815. At the same distance above the Grange Falls they built a Mill, and they, or perhaps the Miller, mounted the rather pedantic inscription "R.H.S.J.S. 1823" which certifies that the promoter was the Right Honourable, Sir John Stewart. Then they raised the status of the Pointz Inn, embossing it with the caption that it bore for a century and a half "Stewart Arms Hotel".

The loom-rush, which had been mostly in the northern town-lands, around Killymorgan, spread in the twenties into south Kerog, principally in all the cottages along an arc from Roughan to Collembrone.

Kelly Groves had noted in 1817 that every farmhouse had a

Page 275

loom or two, but by the twenties, one quarter of the population regarded weaving as their main occupation, if the fathers presenting babies for baptism in Kerog are representative of the whole community.

Between Oct. 1824 and Oct. 1829, 71 of the 253 fathers gave their occupation as "Weaver". The boom was spectacular.

| YEAR | Baptisms | Weavers | % weavers |

| 1825 | 67 | 2 | 3 |

| 1826 | 77 | 7 | 9 |

| 1827 | 49 | 15 | 30 |

| 1828 | 73 | 25 | 34 |

| 1829 | 65 | 21 | 32 |

The Register is so untidy and neglected after J.J. Moutray's arrival in Nov. 1829 that its "Occupation" column cannot be used for statistics. But Thomas Murray's five years of neat and meticulous documentation suggests that the Kerog Linen Industry was growing for 17 years after the Stewart arrival. But, in the next 17 years there was a sharp decline in the number of people regarding weaving as their main occupation. Of course, total production in the district may have been maintained with a workforce reduced by machinery.

Dr. Gillespie has detected from Dispensary Records that weavers seeking medical attention came almost exclusively from the northern townlands. Most extensive weavers were the Carsons of Knockony. Next door, the Stuarts of Killymorgan, whose massive stone memorial stands in Kerog's Wall of Remembrance had at least four looms working. Indeed in 1835 Stuarts were listed in a Parliamentary Report among only five weaving houses in the Clogher Valley. The principle weavers in the southern arc were Armstrong, Arthur, Irwin, and Surgeon.

In 1836 the Stewarts celebrated their Silver Jubilee in Kerog by installing a public fountain at the Linenhall gable. A Grecian figure of Victory flaunts a garland above the inscription

Page 276

|

"Erected by Sir Hugh Stewart Baronet and the inhabitants of Ballygawley the year of our Lord, One Thousand eight Hundred and thirty six." |

And the following year Lewis supplied an index of their achievement—"This town is the property of Sir Hugh Stewart, and contains about 250 houses."119 But their greatest boon to Kerog came a decade later when thousands of peasants survived the Potato Famine. Cottage looms gave Kerogites the pin-money to buy oatmeal.

By 1850 linen production was being centralized, and few considered weaving their main source of livelihood. The last "Weaver" entries on the Kerog Register were Moore and Foster of Roughan in 1845. By 1860, the rural linen industry itself had gone, like those family looms, into oblivion, torpedoed by muslin, and other cheap textile imports. By the end of the century it was a dim memory, echoed in the reminiscence of a local postman. John Dorrian mused in the Ulster Herald of January 1 04—"And who does not remember Bob McFarland of Mullaghbane selling his webs in Ballygawley and Aughnacloy."

As well as the loom-rush, there was a land-rush. Bronze-agers started Kerog agriculture. Scots returning, after 1600, turned it into an industry. By 1750 flax became a major crop when Ulster linen was turned into an industry by families like Colbert, Gervais, Conde, Nimmons and others—driven out of France because they were Protestant.

After Trafalgar (1805) Kerog agriculture boomed. It took ten more years of total war to liberate Europe from the French Dictator, with a growing demand for food and cloth at any price, that Kerog farms were only too eager to supply. In the very year when the son of a Dungannon Lady, General Arthur Wellesley was liberating Spain from Napoleon, Kerog farmers were taking extra land on the hills around the Valleytop to exploit the high prices.120 Families in Collembrone and other lowland districts planted out-

Page 277

posts on the rim of the Valleytop from Fallagherin, to Millex, and even Ballynahaye. These speculators paid excessively high rents confident of permanently high prices for their produce. Prices did rise every year from 1810 to 1815, and farmers prospered on the country's peril.

That Dungannon Lady's son was now Duke of Wellington. Just as the crops were crowning Kerog's acres, he finally defeated Napoleon outside Brussels. For holding his line of battle at Waterloo the Iron Duke gave credit to soldiers from Fermanagh and Tyrone with the plumes in their caps. Their families were not enchanted. Wellington's victory on 18th June 1815 was a body-blow to Kerog agriculture. It was followed by a "great depression in the value of farm produce." Indeed, farmers couldn't sell their bloated crops, nor pay their rents.

Torrential rain swamped Kerog for most of 1816.121 By 1817 Kelly Groves found "dejection and absolute despondency" in the farm houses. Many labourers were hired in November "merely for their board and lodging during the winter months."

For the years of devastating slump and suffering that followed, agitators blamed the clergy, and the clergy in turn blamed the Landlords. Clergy, always a soft target, were obvious parasites on the economy. They raked off the very profit margin which farmers and peasants might have used for farm improvements. The Church's ten per cent (tithe) was a very ancient tax. It originated in Pagan times, and was approved by the great R.C. Council of Trent (1546-64). Clergy actually believed tithes could be justified morally, historically, and even doctrinally.

For the post-war destitution, clergy passed the buck to the Landlords. The Rector of Carnteel branded them as "injurious, demanding and oppressive". Before the end of the century Parliament abolished the tithes, and voted cash to enable farmers and peasants to buy their land, and thus eventually end Landlordism.

Oats was always the staple crop, but the demand for flax grew when the Stewarts revived the local linen industry. The Shaw Mason Report, published in 1820 reported that in Kerog "there is

Page 278

not much barley raised, and very little wheat." Wheat was certainly grown in Richmount in the 1840s.122

"Young Simpleton" was a sample of local enterprise. On 5th May 1834 Printer Robinson in Main Street, Omagh produced an attractive handbill depicting a stylized Groom reining a supercilious stallion—"the property of Mr. James Mitchell of Carren— within one mile and a half of Ballygawley. This beautiful animal stands sixteen Hands high, is a dark dapple grey, with black legs, and switch tail. He was bred from the celebrated hunting horse SIMPLETON, in the County of Armagh, Old Simpleton grand-sire to Young Simpleton was got by Foolfinder, and his Dam by Tug, which was got by Commodore well known to be the best Sire in Ireland, the Dam to Young Simpleton was bred from Old Hob in the County of Fermanagh. The Owner will shew the Pedigree of both.

"Young Simpleton will be let to Mares this season, and the Proprietors of the Mares will have the chance of the Season at the following prices—For a Mare proving with Foal, One Pound, and Two shillings and Six pence to the Groom, for the run of the Season, Fifteen Shillings and 2 shillings and 6 pence to the Groom.

N.B. Young Simpleton will be generally found at the Owner's place as he will not be much in the Public."123

Kelly Groves counted 746 farms in Kerog in 1817. He admits that the Cess Books were not a dependable index of acreage, because farmers minimised their holdings for rate assessment. Except for the 114 acres in the Stewart demesne, the largest holding declared was of 61 acres. Of farms of about 40 acres or more there were only ten. There were 325 mini-farms of 5 acres or less.

By 1879 Favor Royal was employing forty farm workers. By 1900, the pay-roll was down to twenty two. And soon the centre of gravity for Kerog agriculture shifted from Aghmoyle to Augher, when the Co-operative Creamery was launched in 1898 by Andrew Richardson J.P., Robert McNeill, Carmichael Ferrall, and Andrew McMaster who found 30 Sponsors for a Bank Loan to launch the enterprise. Then, on 4th April, 1904 an energetic Scot, John Nish was appointed third Manager.

A month earlier, the Secretary to the Dept. of Agriculture and

Page 279

Technical Instruction in Dublin Castle had a bright idea. He was Thomas S. Porter, son of Ellison Macartney M.P. Porter lived in Clogher Palace, where his grandfather had been Bishop in 1798. He got Montgomery of Blessingbourne and Moutray of Favor Royal to call a meeting in Clogher Courthouse at 2 on Saturday afternoon, the 12th March 1904 "to take measures for promoting, and organizing an agricultural Show."

And so, the first ever Clogher Valley Show was held on Tuesday 30th August 1904 in Clogher Park. There were prizes for cattle, horses, sheep, and swine; poultry, ducks, geese, and turkeys; butter, eggs, vegetables, and fruit. There were also prizes for flower-display, hedge-cutting, spade-work and seed-recognition. The Secretary was Thomas Turner.

The Show Society prospered, and it is difficult to understand why John Lendrum J. P. wanted it closed in 1913 because "it appears to be very doubtful if it is fulfilling a useful function." There was another attempt to "wind-up" the Society in 1920, but when Sir Basil Brooke was appointed President the annual Show was resumed. Mechanisation was on the way. An 1825 Farmer resurrected in 1925 could have found all his familiar cackle, muck, and sweat, but what would he make of the monochrome units of today?

Except for Agriculture, Kerog's industrial tally reads like an obituary. The enduring, the incipient, and the aborted total about ten

|

AGRICULTURE and WEAVING DISTILLING and BREWING GLOVES and CANDLES SPADES and ROPES BRICKS and PRINTING |

For about a century, Ballygawley manufactured alcoholic liquor. Shaw Mason in 1817 and Samuel Lewis in 1837 are among our very few references to this vanished industry. Groves in 1817 did not mention the Distillery—"A brewery has been also established

Page 280

which seems to be going well." Lewis, twenty years later expanded this to "There is an extensive brewery that has acquired celebrity for the quality of its ale, and a large distillery of malt whiskey has been established."

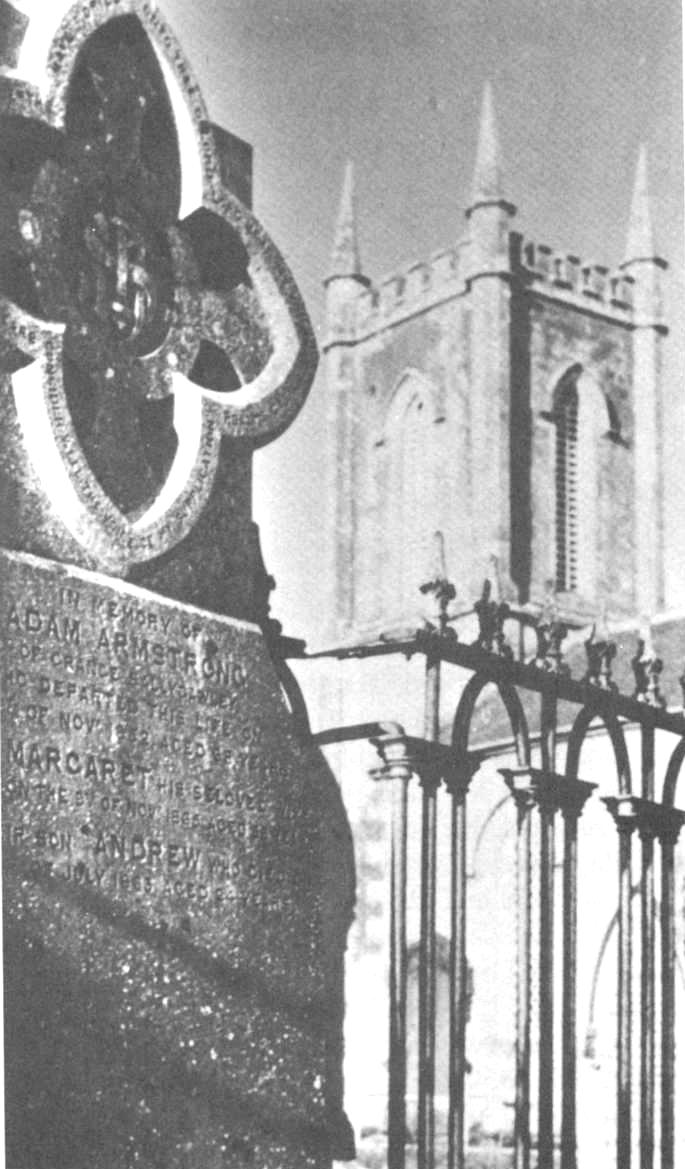

An Alexander Falls was distilling in the village in 1776, but the eventual promoters of this industry were Armstrongs. The family had a brewery in Enniskillen, but seems to be of Kerog origin. There was a Richard Armstrong in the 1631 Favor Royal Muster Roll, and in 1748 an Adam Armstrong with his wife Mary lived in Drumaslagy. The 1782 House of Commons Journal lists four Kerog Distillers, Andrew Armstrong, Alexander Falls, Alex Means, and Terence O'Neal. Andrew Armstrong (1733-1808) was registered as a Distiller in 1788. His wife Sarah bore him at least one son, Adam (1784-1852). Adam Armstrong lived at Grange Cottage with his wife Margaret Fagan, and it was likely he who started Ballygawley Brewery about the time of Waterloo.

The Distillery was on the east side of Lower Main Street, where Loughran's Garage now stands, so Adam brewed his ale on the west side, between the riverbank and the entrance to St. Ciaran's Hall. This extensive industry vanished a century ago, and the sole visible relic is the strong stone wall lining the north side of the Hall entrance. Neither labelled bottle nor barrel has ever surfaced as a souvenir. The Account Books seem to have perished, and most enigmatic of all is the total absence of any "Brewery Worker" or "Distillery Worker" on the extensive 1828 and 1853 Occupation lists. Only four of the operatives listed there may have worked in the liquor industry—Gauger, Cranemaster, Cooper, and Drayman. So, apart from the Armstrongs the only worker whose name we know is written in the Kerog Wall of Remembrance. "Here lieth the Remains of John Taylor, Distiller, who departed this life 9th November, 1815, aged 29 years. He was a kind affectionate husband and father, friendly and benevolent to all."

There are also five old photos of buildings and staff, the nearest thing to tangible evidence that Ballygawley Brewery ever existed. It is even difficult to pinpoint the date of liquidation. Until his death in 1852 Adam Armstrong lived in Grange Cottage with his wife, formerly Margaret Fagan and four sons. The Brewery was

Page 281

|

Page 282

still in the possession of his widow in 1856. She brought the week's takings for Dr. Phillips' wife to count and record in a ledger, according to the recollections of the Doctor's daughter, Mrs Alex Hill who inhabited the Grange Cottage in 1961. By 1877 Laurence Fitzpatrick owned the Brewery. Liquidation must have followed soon. Mrs McKenna of the Post Office often recalled how she saw the Brewery chimney dismantled when she was seven years of age, and that was in 1887.

Dorrian the Postman wrote in January 1904 "For a long time after the regrettable closing of the Distillery and Brewery, the plant and machinery remained in perfect order. The big chimney, towering hundreds of feet in mid air, was 'slaughtered' for the sake of the brick. The greater part of the plant found its way to Cookstown, and I can well remember the six or seven teams of horses, floats, lorries etc. that were engaged in removing boilers, vats, huge wash-tubs, and worms. Financial failure was the ruin of the Armstrong firm."124

Adam endowed Ballygawley Presbyterian Church with a gift of £ 200. He was buried within the high and rusty railings in the centre of Kerog Churchyard. Tradition says two of his sons died in poverty in Dublin, and two in prosperity in Australia. An Adam Armstrong of Inverkeithling, N. Zealand turned up at Kerog re-opening on 2nd June 1974. He had never heard that his family were Brewers. He said his grandfather was Adam Armstrong of Tullycathney, Castleblaney. The Brewery family are said to have had forebears in Tydavnet.

The Armstrongs also warmed Kerog hands. For approximately sixty years, 1790-1850 the only Glove Factory in Ireland was owned by Richard Armstrong and Alexander Falls Hughes, Kerog Churchwardens in 1815 and 1829 respectively.

Richard Armstrong (1754-1836), probably a son of Adam Armstrong of Drumaslagy, bought property in Grange in 1798 from Hamilton-Gorges. With Alexander Falls Hughes he started making Gloves in the Brewery precinct.

| Chapter 8 ends on Page 315 |